Continuing on

So without further ado, i’ll jump straight back into it, following on from the previous post which can be found at https://theluciferianrevolution.wordpress.com/2013/09/19/review-and-summary-apocalyptic-witchcraft-part-one/

For those who are reading this post first, it probably wont make much sense without the context of the previous one. I was summarising and reviewing the chapters, so will first complete that before heading on to a final conclusion as to the book as a whole.

A Spell To Awaken England

This chapter is the chapter that I personally find the hardest to read, and summarise, in the book. This is due to me possessing only a cursory knowledge of Robert Graves, Peter Redgrove, and Penelope Shuttle, having only really read some of The White Goddess and possessing limited knowledge of the other authors. As such, despite this being a long chapter, I will only be able to offer a cursory evaluation..

The chapter revolves around the importance of poets, poetry and the poetic tradition in the expression of Modern Witchcraft. In this section, the author elaborates how to him, the poets are responsible as much as any witch, perhaps more so, for tapping into the currents of land and Goddess . He writes this is a passionate fashion, firstly addressing the said Robert Graves and his book The White Goddess. As we will see elsewhere, he argues that this text is an important myth that reaches out to hit a fundamental truth, helping to further the modern witch revival, despite its accuracy. However he warns that as its efficiency is eroded due to it not being seen as powerful anymore thanks to an academic assault about its veracity, a new generation of poets are needed to reach down and return with unashamed experiences and bring them back in raw form to shake up, shock, and revitalise us with a similar, if not greater kind of vigor and power.

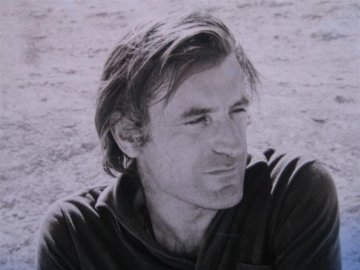

Renowned Poet and Author Ted Hughes

The author from the third page onward goes onto to discuss in length the importance for him of Ted Hughes. He sees Hughes as a visionary – someone who managed to tap into the spirit world and drag back important messages and visions, albeit leaving him a bloodied, harrowed and to a degree a broken figure, someone who has paid for the knowledge he has obtained. He goes on to relate this as a shamanic gift and curse, explaining to us how the process is necessarily painful in many aspects, to really be able to channel anything and relay an esoteric message.

In this chapter he uses many examples of animals, which Hughes used in his work, and how he relates these to totems, messengers from nature that Ted Hughes has given voice to whilst maintaining their animalistic, unashamed and of pure natures. One particular part stands out for me here, where the author describes the use of the fox, an animal present in many of Hughes works, to point out the impact of his poems and delivers a powerful visceral image. This message is simple and clear – pure, raw oracular message that doesn’t lend itself to dissection without severing it from relevancy. This I think is demonstrated well from the following quotes from the chapter, the former from the author, the second from Hughes himself.

‘Hughes ceases studying literature after a visitation by a burned and bloody human-handed fox that delivers the pronouncement, Stop this, you are killing us. This theriograph is a magical messenger, not some prim angel made out of too many books, but a nature spirit. Poetry is not to be dissected to death, and neither is magic, nor, for that matter, sex.’

‘Imagine what you are writing about. See it and live it. Do not think it up laboriously as if you were working out mental arithmetic. Just look at it, touch it, smell it, listen to it, turn yourself into it’

As someone who has only read some of Hughes works, and was only partially exposed to the others, I still found this chapter highly effective in discussing how important mythos, and direct experience brought to life through pure unfiltered language is over an approach that through careless over intellectual analysis, orthodoxy, desensitisation, and deconstruction sees such messages stripped, diluted, and robbed of much of their meaning.

In some ways this can be seen as a continuation of The Cup, The Cross, and The Cave chapter for me, with poetry being espoused to be the purest voice we can give to relate these deep, and meaningful experiences. I found that even with my limited knowledge in the area, this was a powerful and important chapter that gave voice to some ideas that i was struggling to express.

The Thought Fox by Ingrid-Karlsson-Kemp

The Scaffold of Lightning

This chapter deals with the Horned God, the Devil, and how and why he has remained a powerful figure and is important to modern witchcraft. It begins with a small definition, ‘the Devil reveals a narrow path out into a dark wood.’ before continuing onward, ‘Nor does it matter that at times he seems the Lord of the World, at others a more intimate local spirit. It is what he shows us that counts’.

From here, the author talks about the absolute power of the devil, that no intercessor is needed between witch and spirit. Through this, he demonstrates the power of Lucifer to show to the would be witch the path into the mysteries. It goes on to say that it is time that modern witchcraft as a whole paid the devil his due, and not to entirely white wash him of his antinomian aspects in the process.

The author then goes onto discuss the traditional medieval image of the devil as a demonic aristocrat, the last resort of the desperate who have turned away from the church, choosing a different master. He goes onto reminding us that this is a reflection through a society dominated by feudalism, and psychological warfare.

‘What we must remember is that the accounts we have, almost always trial testimony, are performed as a penitential theatre of accused, judiciary, nobility, and clergy. Such a court is convened on a field of folklore, myth, legend, invention, and dream drawn out through torture, threat and false hopes’

However rather than simply say thus the devil is baseless due to the above, the author goes on to cite the following quote from Emma Wilby on The Visions of Isobel Gowdie.

‘Increasing interest in the folkloric dimension of witchcraft beliefs is leading scholars to consider that confession-depiction of the Devil might be rooted in genuinely popular ideas about embodied folk spirits, such as fairies and the dead’

He comments on this with the following:

‘Note the deliberate use of the word embodied. This is dynamite. It gives the Devil an existence that is recorded, experienced, and blooded in the folk and land’

The Great He-Goat by Franciso Goya

He goes on to say that that thus the devil is an aggregate, with the original folklore merging with the christian concepts and that they are bound together.

He says that witchcraft therefore must understand the contributions of European demonology and such magickal traditions, and not reject the fertile growth of new strains of Diabolism. He remarks that witchcraft should learn from the modern satanic ‘movement’ that has arisen and been drawn through popular culture, and understand the impulses that drive them whilst avoiding the dualistic trap that can easily occur within such belief systems.

‘The mistake made is often inversion, a potent formula of witchcraft in itself, but one that after breaking the social bonds often simply reforges them and chains its adherents to a dualistic script’

From this the author goes on to describe how the Devil is protean and changes as we change, taking on different masks. He argues that we cannot simply leave him behind to engage with a horned god of our forebears so easily, arguing that the masks of the Gods of the past came form the soil and social conditions, and that ours must also come from our own age.

From here he goes on to relate how the story of the God of Witchcraft is related through the story of the Devil, just as the hatred of women within Revelation tells the story of the Goddess unwittingly through Johns twisted psychology. He goes on to explain that ‘The Devil is a particularly European trickster myth’. The author paints a scene of how the Devil was created in his current from through Christianity replacing Paganism throughout Europe.

The Fall of Lucifer by Gustave Doré

As he develops this, he goes on to state how this image is now useful to the craft in the described age of human disenchantment and apocalypse as described in the previous chapters.

‘It is at these crossroads, translocated from lost Jerusalem and before that Babylon, that the division between high and low magic, heretic and mystic, magus and necromancer, magician and witch. Our identities merge and are lost in the dance that we can now properly call the witch cult. Who could preside over such a gathering other than the motley Devil?’

After covering these points, the author goes on to ask us a deep question.

‘Who then is this Devil? A simple answer will not suffice, the answer is complex, personal, and the resolution of polarity..’

In light of my own posts on this issue to clear up my own approach and answer to this question, wherein i describe the Devil as simply a powerful face of the antimonian aspect of the Horned God focused and concentrated through Christianisation , i found this a highly interesting read and accurate from my own perspective.

The Children That Are Hidden Away

With the Devil addressed, the author then uses this subsequent chapter to deal with the Sabbat. This chapter is powerful, and outside of The Cup, The Cross, and the Cave my favourite chapter, due mainly, admittedly, to my own biases towards and interest in Necromancy.

The opening paragraph sets up the chapter fittingly:

‘The Sabbat is the love feast of the Witchcraft. It is the central rite by which we have been both identified and condemned. Our revels have been daubed in the blackest garb…. This list of atrocities is why many modern proponents of witchcraft have been quick to distance themselves from what has been considered a demonological imposition upon a simple folk faith’

He then brings up Carlo Ginzburgs work, which he believes by attempting to clean the Sabbat, similar to the attempted ‘cleaning’ of the Devil in the previous chapter, is misguided. He argues that rooted in the Sabbat, in all its aspects, is a deeper truth that can be explored and revealed. He argues, in his own words, that his ‘thesis is that the Sabbat is the survival of Mystery cults and a resurrection mythology which is concealed in the Great Rite itself, the mystery within the Mystery… I want us to celebrate the Sabbat again, not by standing unsteadily on a stack of books, but on the Sabbat mountain itself’.

Thus he begins his exploration. First he describes the Sabbat in broad terms, stating that ‘the Sabbat is far more egalitarian… it strips away difference. It summons us. This calling is the inner aspect that defines a witch, rather than the outer social aspect of the accusatory pointed finger of condemnation. The first flight to the Sabbat is very often a spontaneous event. One which is not mediated by coven or ritual. It is a lucid, though often shocking, transfiguration’.

From here he begins to talk about how the Sabbat experience, through such figures as Johannes Wier and Reginal Scot became associated with delusions, and that in an increasingly materialistic world, the experience has been devalued, and is instead seen in the terms of a solipsistic, neurotic experience. The authors reponse is to reject this, and he goes on to say that it is this zone, the Sabbat experience, which must be again placed as the core practice within the craft. He cautions again that to remove the ‘forbidden’ aspects is to excise it of much of its meaning.

He then moves onto discussing entheogenic drugs – the salves and flying ointments that were often applied to induce such experiences within the witch. He goes on to explain that although indeed such salves were used, this does not discount or cover all the cases of Sabbat flight. He specifically addresses the processes of the salves application as more than simply the reaction to polypeptides, and notes that they are also poisons, able to take us to the state that exists between life and death. He goes on to speak about this shamanic liminal state, which can be brought about by many techniques and circumstances such as fasting, and ritual practices.

He ends this section of the chapter decisively with the following:

‘My considered position on whether the Sabbat is physical or not is that the question itself is absurd. Witches do not divide the states of sleep and dream and vision. This magical monism is something rare in literate and modern minds… It is a shamanic conception that must be embodied in our witchcraft.. if it is to both have and provide meaning’.

The Witches Sabbat by Francisco Goya

From this point onward, he begins to talk about the nocturnal associations of the Sabbat with the dead, and how the witch becomes one of them during flight, assuming the forms of ‘our [the practioners] dead, our blood, our totem’. It is through the ingredients of ash, blood, milk and dew heavy moon he argues, aligned with the necromantic and lunar aspects of the feminine this transformation is most facilitated, and goes on to ascribe timing as being critical, fixing the time most ideal for the Sabbat at the full moon. He goes on in this manner to describe the Sabbat as far older than a bastardisation of the Jewish Sabbath through Christian propaganda, instead tracing it back to its Babylonian origins from the Akkadian word Sapattu or Sabattu. It is here that the author mentions for the first time the number 15, relating it to Inanna’s descent to the underworld and other points of significance that he will go on to elaborate on in a later chapter.

He then with this said moves onto describing the sacred mountain of the Sabbat:

‘We are journeying in our transformed bodies to a singular destination, the sacred mountain. This is the vision of the Grand Sabbat. The participants come from the flung compass points, there is no uniformity, but quite the opposite, all heresies are on the wing’.

He ascribes the name kur to this mountain, where the Sabbat takes place a word the Mesopotamians used to describe it, a place that is at the same time both peak, and underworld. Here he begins the comparison in earnest, drawing comparisons between the medieval Sabattic images and Enkidu’s account of the underworld from the Epic of Gilgamesh. He draws further necromantic comparisons between the hollow kur and the skull, and how both represent an external and internal transformative process

Lastly, but not least, the author asks the question to what end is the Sabbat partook in? He then answers it by describing what happens at the Sabbat, which in itself reveals the answer. The author selects themes common to all the tales of the Sabbat, such as dismemberment, feasting, dancing and sex. He goes deep into each of these specific sections, revealing aspects to why they are important, what they represent, with themes of ecstasy, birth and death, and the dead all combining to show quite effectively the importance and direction of the Sabbat. That is, its role as the great rite, where in mixing of these elements arises the cycle of life, a divine resurrection, where upon the living dance the dance and the dead are reborn into the world.

Sabbat et cuisine de sorcière by Jacques de Gheyn

This section is powerful and difficult to cut down into a more concise form, so I’ll leave it to the reader to explore this part of the chapter in more depth. It successfully delivers however, I believe, the powerful intention the author is trying to make, and is definitely something that resonated with me.

A Wolf Sent Forth to Snatch Away a Lamb

With the subject of the dead, and the devil, covered, the author goes on to the topic of Animal Transformation, primarily through tales and talk of the wolf and of lycanthropy. Whilst many of the chapters are based on the female, lunar, dominating current on Witchcraft, this chapter deals with the more male aspects, of which the author brings an interesting perspective.

The chapter starts with several paragraphs laying bear, in poetic terms, the hunger of raw need for man to be ‘rewilded’, and the reader brought into the imagery of the human as animal. He then raises and answers effectively a none too basic question, which is where men fit into his mythic topology of Witchcraft, which the author himself as being, due to the Lunar links, primarily a womans affair. He answers it thus:

‘.. the answer has already been given in the song of the wolf. Men are excluded from many of the rites of witchcraft. Men do not. Thus our mysteries differ from those of women.’

He then goes on to describe the early accounts of Lycanthropy involving male witches. However, to delve deeper, he first cautions we must be careful with this train of thought, reminding us that women have also assumed wolf form in the past, and that the ‘wolf has too often been rune-hooked into a totem that the wolf itself would not recognise’. He cautions us at accepting the wolf, as the icon it has become, due to it often being seen as a left handed path image of domination that suppresses the supposed weaker, emotional feminine self.

He goes on to describe this wolf image, describing it as socially broken, the images it projects of abduction, murder, and rape not describing accurately, nor capturing the essence of the wolf. He describes such a lone wolf as sick, and makes a parallel with the witch at the pointed finger , describing the wolf as a male representation of the same ‘blame’ game.

He goes on to describe the totemic wolf as he sees it, animals that taught us how to hunt, ambush and lure, ‘mighty hunters who sing to their mother moon’. Here he also highlights the social structure necessary in the wolf, highlighting parallels between us.

He again brings up the theme of being rewilded in this context, and describes how many items from wolves were meant to have many magical powers. He describes how even now this lycanthropy occurs in dream and dance, and points it out as the image of the Northern winter sun, the downed stag representing the summer king subdued and dominated. Again he makes the comparison.

‘The men who go forth as wolves are the retinue of the divine huntress, a reckoning at large in the land, a stormy night that beckons to the bold whilst the dogs lie sleeping in their beds.’

It is here he begins displaying them as ghosts and teachers, linking them to the ancestral dead, our familiars, as warriors, transformed witches, and agency of the Goddess. He links the hunt to nocturnal vengeance, sexual voracity, ritual actions, animal transformation to blend in and sending forth the fetch, all occurring under the full moon. As he describes it, this Sabbat like imagery ‘is the same familiar unfamiliar territory’. That is, the territory of truths preserved, just as the Sabbat was, with a malevolent face.

Werewolf, artist unknown

It is here he delves into the associations the wolf has had with the warrior cults of northern and central Europe, and how wolf skins were seen as sacred, and used as amulets. He again sees how this was usurped, and turned into the raw, diabolic imagery described above as it was subsumed into association with diabolism by the church. Here, retaining its essential nature, but becoming another ‘part of the sorceress conspiracy’.

He goes in to describing how this is similar to the bear cults also found in Europe, and the use of drugs such as muscaria to help drive a divine possession and frenzy within its adherents. It is here he reveals his purpose, describing war as a special kind of hunt, the male parallel to female blood shedding. He goes into this in great detail, and again, its not something I can appropriately summarise in a short manner. One quote however, I feels explains some of the authors intent.

‘The man or woman who becomes a wolf is engaged in a cyclical transformation that takes them outside of culture. For women this a given, they are periodic, but for men this requires ritual action. The WItchcraft of men is thus built and dependent upon the blood of women. Blood must also flow for men to be initiated. Whipping, sub-incision, scarification and tattooing are among the ritual actions that can be performed. This does not imply simple masochism’

It is from this image he moves into discussing truly the ‘resocialised wolf’, using it as a metaphor for the reintegration of wild aspects back into our own natures. He goes on to describe this process in degrees. First he tackles the wolf image, again using metaphor. In this, he states that what we need aren’t lone wolves, but instead socialised, integrated wolf packs, packs that are loyal to the Goddess. He regards this as part of the inversion of the wolf’s image, no longer an image of dominance, male dominance and female suppression, but an elevation and joint synergy between both. On this he writes:

‘What if we become wolves in her service? I suggest that Witchcraft represents such an inversion, a reversion of the patterns of abuse and domination that … have divided the sexes in setting men upon women’

From here he goes on to describe the kind of animal transformation he sees, based on this inverted pattern. In this section he engages us to think about re embracing our physical natures, embracing our physical bodies. He warns us that we are in danger of ridding ourselves of our bodies like ‘cartridge cases’, and goes on to detail the sacredness of ecstatic and excited states. He explains that these have been under assault in common thinking, especially in some circles which overly embrace eastern mysticism which discards this in bodily rejection. He again comes back to the entheogens, but this time talks about the sacred stimulants, as opposed to those used for night flight, again reminding us to not make an artificial distinction between either. It is through both body and spirit, he argues, that these states are accessed, and the interaction achieved.

Gray Wolf by National Geographic

It is from here he goes on to relate about Lupercalia, and goes on to discuss the mighty dead and the Wild Hunt. He relates how the wild hunt fits into the topography, not as a simple new moon event or full moon event, but instead a complex mix of both, of both the Sabbat and Bloody Moon. He then goes on to seal this wolf tale as the final piece, that completes both halves of the mythic structure he has been constructing. He gives us an collected, summarized version of this in the text, which i think is very revealing. The last part of the text drives home why this is important in our age to understand the metaphor and image of the Wolf and our spiritual Ancestors, leaving us a great image with the end of a revealing chapter.

‘The wolf [is now] the shadow of man. We have hunted the same prey. But we have fallen out with these brothers and sisters, to our detriment and their extinction. Let us decide to play the game again. Let us turn over the cards of Dame Fortune. XVII La Lune reveals even dogs are transformed on certain nights into their ancestors, and that it is blood which provides the key. Through this slim fence slip once more the gaunt wolves into the city, our throats erupting into song.’

Fifteen

In this chapter the author begins to discuss the Goddess, leaving perhaps the topic to later in the text than we might have expected. It is here we see the revealing of many symbols of the Goddess, of the authors own personal mythological topography, which has slowly been threaded through the work.

The chapter opens up with poetic imagery of the Devil as Initiator, who has brought us to meet with the Goddess in the dark wood, stripped down to nothing but our skins. From here, he goes on to describe the cyclical life of the moon with similar imagery, referring it to the cycle of life, and the circle that connects all things. He then relates to us that the Goddess being seen as the moon is a mistake, and that instead that ‘She is Time Herself’.

He goes on to relate how its Time that encapsulates all the moon phases, the aspects, with the Sabbat marking the ‘moment of Immanence’ within the ‘cycle of flux and flow’.

From here, he goes on to explaining this in greater detail, and reveals that the Goddess is never named, only referred to in oblique terms. These terms being ‘ciphers, blinds, riddles, points of origin’ and other aspects. He then goes on to describe the most enduring one, that of Fifteen, and describes it as important as the easiest way to envision her outside of cultural forms that can compete and clash. From here he goes onto describing the symbology behind and the integration of the lunar calender, revealing the number 15 and 13. These numbers, he relates, arise from the number of the day the moon falls on in each lunation and the number of lunations in each full year respectively. He goes on to relate to us how this is integrated with our environment and ourselves.

‘For the lunar calendar to exist required it to have embodied meaning, one which meshed into a series of species and events, of salmon runs and rutting deer and moulting bison and sleeping and waking bears. It is a cycle of seasons over which a Mistress of the Beasts prevailed. For us to engage with the mythic, we must be attuned to its many pulses over which the moon rules. But crisis intervenes.’

He relates how when the human race moved from being a purely hunter gatherer race to a one based around agriculture, this calender necessarily followed, along with the associated underlying mythic architecture.

‘Now it was not simply the salmon run, the story of the first flowers in the meadow, but a million tributary rivers carrying us on. Her sex runs wet … And so our Goddess slips from the reed banks and finds herself within a second cave at the temple heights’

It is here he carefully and considerately makes the connection with Ishtar, and delves deep into the symbology and meaning which embodies the number 15, the sacred marriage between the sun and moon the comes to its height on the full moon, and the day which Ishtar began her descent into the underworld.

Queen of Night Relief, The British Museum

He goes on to describe Inanna-Ishtar as ‘the primal spring’ of the origin of the Goddess of Witchcraft, He goes on to directly link her to many other concepts of the Goddess. He explicitly singles out the greek goddess Hecate being another face of Ishtar, and highlights other figures such as Medea, Circe and Artemis as arising from out of significant Akkadian cultural influence.

He goes on to say how Ishtar has been misidentified not only in ancient but also in modern circles. He gives an example of this in the fact the Queen of Night Relief is commonly linked with Lilith, herself ironically arising from the Akkadian concepts of the Līlīṯu, a class of female demons.

He goes on to relate how although this could be a useful aspect, that it narrows the scope of the Goddess into simply a malevolent force, when she is infact a master of all directions. He associates the Lilith myth and angle as therefore being potentially constricting.

Again, he goes on to talk about the dark moon, how it runs with blood and how it should not only be seen as a curse but a gift, and reinforces the importance of 15 as the centre of the cycle and the axis mundi where the aspects meet. He discusses Kali as a overpowering face of the rotting goddess, warns us of appropriating her own rites and asks us to turn inward to find our own, western analogues. He describes this thus:

‘As our focus has been on the central rite of European witchcraft, namely the Sabbat, this has been occluded. Perhaps the best way to signal its importance and very nature is in this absence and deliberate omission. It is the shadow beneath the wings of this text, but enfolded as a blood seed at the heart of the Sabbat.’

This flows into the paragraphs describing the immense disruptive power of the eclipse. In the final paragraphs, he describes and gives voice to what he sees as the overriding presence of the Goddess and sums it up in the following manner.

‘She is not external. but is enfleshed … There was never one goddess of witchcraft, but rather a thousand Ishtars: milk white, blood red, lamp black. There can never be orthodoxy. We are simultaneously possessed, annihilated, and forever outside of Time.

She is Immanent.

She dwells within us.’

Kali by Raja Ravi Varma

Hic Rhodus, Hic Salta!

The last chapter in the book, Hic Rhodus, Hic Salta, is an effective ending which manages to, in my opinion, sum up the main messages in the book in a clear and concise manner. The epigram used to name the chapter is described at the end, but to make the summary of this final chapter more approachable, ill detail it here.

The phrase Hic Rhodus, hic salta, originates from the Latin version of Aesops Fables. Literally translated from the early ancient Greek phrase, it means ‘Here is Rhodes, jump here!’. It relates to one of the fables, where an athlete boasts that he once achieved a seemingly impossibly large jump whilst competing at Rhodes. A bystander challenges him to dispense with the accounts, and simply prove himself by demonstrating the jump right there, on the spot. Thus the term came to be a proverb, meaning ‘Prove what you can do, here and now.’

As hinted at by the book, this is the conclusion that this chapter, and that the book reaches. The author gives another version of the phrase as the final words of the book, ending it all on a simple but powerful note. Within this chapter this message resonates. It is not presenting to us a request, or even offering advice, but a challenge. To meet this challenge, the author suggests that modern witchcraft needs to concentrate on imbuing itself with Orientation, Presence and Imperative.

He goes into detailing these length. I will cover these briefly.

He describes Orientation as embracing animism and finding a shared mythic topology on which to find common ground as Witches. He believes that through the words of the poets, and through the Sabbat, Night Flight and Animal Transformation this has been found, and through the revealing of the Goddess and Devil revealed as One. He describes this as being a ‘simple and not prescriptive’ topology, which acts as a way for the witch to connect to the world through their own, internal interface. From this, he states that the doors are opened within and without, as we develop on top of this our own means of interacting with the world in a way that is based on connection as we interact with All, rather than fall into some baseless solipsistic reverie.

He then goes on to describe Presence. He begins this section by saying that we must not make the mistake of believing ourselves to be apart from the physical world, and make a fatal mistake between the physical and spiritual. He reminds us that animism sees no such divide, and therefore does not strip meaning from the physical world to abstract it away. Its through this integration, and through the paradox of travelling in and through our our bodies at night we can reach the Sabbat through the gates of dream. As such he asks us to re-sanctify it, strengthen it, and grow active again, so we can move renewed. He gives us a taste of why presence is important within the following paragraph.

‘The mythic is not an overlay, it is the worn cupolas in the rock quoits stacked in the barren moors. It is the black earth of the barrows. The earth is pregnant with meaning, with tumuli and foreboding entrances slanting down into the underworld which we have crawled from on skinned knees into solstice morning dawns. This is magic, this is what demands our presence, and furthermore this is what is at stake’

The final aspect covered is Imperative. The author uses the last two to reinforce this aspect effectively. He goes on to relate how we cannot escape into solipsism now even if we wanted to, and instead are demanded, forced, to take an active stance. He says that we are defined by not contemplation but engagement. The imperative leads to this engagement on its own, due to the fact that true witchcraft is grown from need, not want, and that in our current time it is needed more than ever. He shows us that since our shared experience is based on animism, we must defend a world that is increasingly trampled, and the imperative is in that struggle. The struggle that if it is lot, our familiars, our family, will be irreparably injured or killed.

On this powerful call to action, and bringing the entire thesis to a powerful conclusion, this chapter concludes thus.

‘Here is the Rose,

Dance here.’

Conclusion

Writing this review has been long and difficult. However, I felt it was more than necessary after receiving, and reading this book. That is the highest compliment I can give it – that it exceeded my expectations, and was a captivating read which seemed to give a voice to many things that already resonated within myself.

The author describes the book as a revolutionary book, as a challenging one that many have found issue with. To me this is almost difficult to imagine, as it seemingly simply described what I have been consciously and unconsciously feeling ever since my own initial encounter and introduction to Witchcraft and Paganism in general.

I honestly think that it is an important work, and that it should be acquired by anyone who calls themselves a witch or is interested in modern witchcraft. It is a highly inclusive, revealing and passionate work that I think will only be increasingly referenced and appreciated as time goes on.

I’d also like to thank Scarlet Imprint for linking to my review, and enjoying it. It means a lot to think that my own personal take would be read and warmly received by them. I look forward to receiving more of their books in the future, if they are of similar quality (of which I have very little concern over).

As far as the blog is concerned, this will most likely be the last long post in awhile, due to my personal circumstances changing (for the better) leaving me with a lot less free time. I’ll be detailing this in a another, short post, that should hopefully come soon.

Thanks for reading as always.

~S~